Species Index

Key Facts

Length: Up to 27 metresRange: Global distribution, absent from the Arctic Ocean

Threats: Pollution, aoustic disturbance

Diet: Fish and krill

Fin Whale

Latin: Balaenoptera physalus

Gaelic: Muc-an-scadain

Physical Description

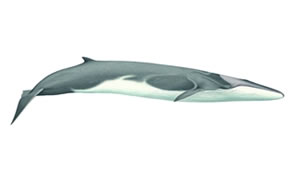

The fin whale is the second largest of all cetacean species, and can reach 27 metres in length when fully grown although animals in the northern hemisphere are usually smaller than those in the southern hemisphere. It has a streamlined body and the head represents about a quarter of the total body length. Unique among cetaceans, the fin whale’s lower jaw is black on the left side and white on the right side, and is an important identification cue. The curved dorsal fin is set two-thirds of the way along the back, and is visible shortly after the blow upon surfacing; the blow is tall and columnar. Colouration is generally dark grey on the top surface, with white throat pleats, a white belly and white underside to the tail. There is a characteristic pale grey ‘blaze’ on the right side of the head and subtle chevron patterns along the back behind the blowholes. Tail flukes are broad with a distinct median notch and slightly concave trailing edge, and are rarely raised out of the water when diving. The life span of a fin whale may be 85 to 90 years.

Habitat and Distribution

Fin whales are widely distributed throughout all major oceans but seem to favour coastal and shelf waters between temperate and polar regions. Little is known about their movements and migration, and whilst it is thought that some seasonal migrations take place, they appear to be complex. Sightings in the Hebrides are very rare and generally occur during summer months, suggesting that the whales move into our inshore waters to take advantage of rich food resources at this time.

Behaviour

Fin whales are among the fastest of the large whales and, despite their enormous size, are capable of reaching speeds of around 25 mph and may travel as much as 90 miles a day. Fin whales are normally seen alone or in small groups, but can form larger aggregations on their feeding grounds. Whales produce loud, low-frequency vocalisations that travel long distances through the water and may be used to communicate with each other. Fin whales can dive to depths of over 200 metres, which is deeper than either blue or sei whales. Very little is known about the behaviour of fin whales in general and rare glimpses of them in the Hebrides are normally of travelling and feeding animals.

Food and Foraging

Fin whales feed on fish species such as herring, mackerel and cod, squid, as well as krill. This diet probably varies between areas and seasons. Huge quantities of food and sea water are taken into the mouth, which then closes to allow water to be pushed through the baleen plates. These stiff structures act like a sieve to catch the prey, and then a huge tongue sweeps the food down whilst the water is expelled. Fin whales in other areas of the world are often seen in coastal and shelf regions, where areas of upwelling and interfaces between mixed and stratified waters provide rich feeding opportunities.

Status and Conservation

The total fin whale population in the North Atlantic is estimated at 35,000 to 50,000; numbers were significantly reduced by whaling activities during the 20th Century. Fin whales are known to carry high levels of bioaccumulating pollutants such as heavy metals and organochlorine (pesticides) compounds; these have been demonstrated to accumulate with age and to transfer between generations via lactation. The health implications for accumulations of pollutants in all cetaceans are still poorly understood. Fin whales may also be negatively impacted by noise and disturbance from vessels and other underwater noise, which may mask their social sounds. Fin whales are protected under UK and EU law, principally under Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004 and by the 1992 EU Habitats and Species Directive.