Species Index

Key Facts

Length: Up to 9.8 metresRange: North Atlantic Ocean

Threats: Marine litter, acoustic disturbance, pollution

Diet: Mainly squid

Northern Bottlenose Whale

Latin: Hyperoodon ampullatus

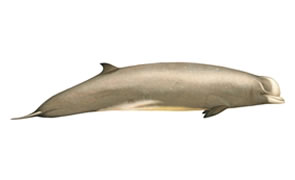

Physical Description

The northern bottlenose whale is a beaked whale (family Ziphiidae) that has a very distinctive bulbous melon (forehead) and a dolphin-like beak. In males, the flattened melon is often white, whilst that of the female is more bulbous and grey in colour. Fully grown adults may grow to 9.8 metres in length and live for up to 40 years. The body is large and rotund with a small falcate (curved) or triangular dorsal fin, often featuring a pointed tip, positioned far down the back. The broad tail fluke has a concave trailing edge and no median notch. Adult colouration, like many cetaceans, is countershaded; the back and sides are dark grey and the belly is lighter, a pattern that is thought to provide camouflage. Adult females commonly have a collar of paler skin behind the blowhole. There may also be some scars on the skin. Male individuals possess two, slightly forward-pointing teeth at the front of the lower jaw; females have no teeth.

Habitat and Distribution

Northern bottlenose whales are deep-water specialists found in the North Atlantic Ocean. They occur in small numbers off the Northern Isles and Western Isles of Scotland, and off the west coast of Ireland. Their oceanic lifestyle has led to a gap in our knowledge about the general ecology of beaked whales, with many aspects of their lives remaining a mystery. Records of this species in the UK also include stranded animals, including the juvenile female whale that swam into and stranded in the River Thames in January 2006. Northern bottlenose whales may undertake seasonal movements within their range, but these movements are likely complex and remain poorly understood.

Behaviour

Sound appears to be very important to northern bottlenose whales; they make a complex range of calls for navigation, foraging and communicating with one another. They usually occur in groups of four to ten individuals and are thought to be quite social animals that have been observed demonstrating care-giving behaviour. Boat users have also commented on their curious nature when they slowly approach and circle vessels.

Food and Foraging

The preferred prey of the northern bottlenose whale is squid, and they can dive to at least 1500 metres for up to two hours to catch their prey. Their diet is apparently very varied, probably according to area and season, and may include fish (such as herring) and invertebrates (such as prawns and sea cucumbers). Other items including pieces of wood, shells and stones have been found in the stomachs of these animals, suggesting that they feed along the sea bed. Teeth are obviously not required in their foraging habits, but it has been suggested that the beak may be used as a ‘plough’ during sea-bed feeding.

Status and Conservation

The current population status for the northern bottlenose whale is unknown. Populations were depleted by commercial whaling, particularly during the 20th Century. Current threats include the accumulation of toxic pollutants such as organic pesticides in whale tissue and organs, entanglement in fishing nets and marine litter, and noise disturbance, which interferes with their complex echolocation and use of sound. It has been suggested that sudden loud noises, such as those emitted during seismic operations, may startle beaked whales during deep-dives and cause them to return to the surface to quickly; much like a human diver, this can result in nitrogen bubbles forming in the blood vessels and organs of the whale. As a squid eating cetacean, northern bottlenose whales may swallow plastic bags mistaken for prey. Plastic was found in the stomach of a Cuvier’s beaked whale that stranded on Mull in 2004, and it is likely that this issue also affects other species of beaked whales, such as the northern bottlenose whale. Once ingested, plastic may accumulate in the stomach of the animal causing starvation and eventual death. Northern bottlenose whales are protected under UK and EU law, principally under Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004 and by the 1992 EU Habitats and Species Directive.