Species Index

Key Facts

Length: Up to 18 metresRange: Global distribution, except for extreme polar regions

Threats: Pollution, acoustic disturbance, entanglement in fishing gear

Diet: Variety of squid, octopus and cuttlefish

Sperm Whale

Latin: Physeter macrocephalus

Gaelic: Muc-mhara-sputach

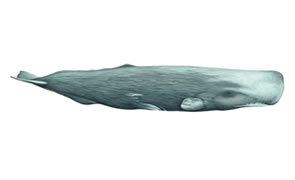

Physical Description

The sperm whale is the largest of the toothed whales. Males can grow to 18 metres in length, whilst females can reach about 11 metres. The large, square shaped head represents about one-third of the total body length and contains the spermaceti organ; this organ is filled with a waxy liquid called spermaceti, which is involved in sound production and echolocation. The lower jaw is narrow and contains 20 to 26 pairs of conical teeth, which fit into sockets in the top jaw; there are no teeth in the top jaw. On top of the head, the s-shaped blowhole is positioned to the left and angled forward, which produces a distinct, bushy shaped blow. Sperm whales do not have a true dorsal fin but there is a small triangular hump, behind which a row of bumps extend along the back toward the tail. The tail fluke often has nicks and notches that can be used to identify individual animals. Skin is wrinkled and dark grey or brown in colour, with white patches on the belly. There may also be circular scars on the body caused by squid suckers. Life expectancy is estimated to be at least 70 years.

Habitat and Distribution

Sperm whales have a global distribution, although it is thought that only adult males occur in the polar regions. They are mainly associated with deep water, which harbours their preferred prey, and are commonly found over submarine canyons and continental shelf regions. The UK has the highest number of sperm whale sightings in Northern Europe; sperm whale sightings are very rare in the Hebrides, just one or two reports every year, because they prefer the deeper waters beyond the Outer Hebrides.

Behaviour

Sperm whale social structure involves groups of females with their young male offspring, bachelor herds of juvenile males and solitary adult males. Sightings in the Hebrides are normally of solitary animals. When feeding, sperm whales make long dives as deep as 2,500 metres for up to two hours, and often return to the same place on the surface. A diving sperm whale characteristically arches its back and raises its tail fluke. Sperm whales can be seen ‘logging’ at the surface between dives, which is apparently a rest or recovery period. Sound is very important to sperm whales, as they use echolocation for navigation and to locate food in the dark ocean depths. Males also produce very loud vocalisations, known as ‘clangs’, which are believed to be a mating display. There are several records of stranded sperm whales around the British coast, including the Hebrides.

Food and Foraging

From analysing stomach contents, scientists know that sperm whales feed on 40 different species of squid, octopus and cuttlefish, and most famously dive to incredible depths to hunt giant squid measuring up to 12 metres long. Their bodies often bear scars inflicted by the squids’ suckers and beak. In a single day, an adult sperm whale can eat as much as one ton of squid, but they also feed on some fish and crustaceans. The exact diet of sperm whales seen in the Hebrides is unknown.

Status and Conservation

Sperm whales were once the target of commercial whalers because of the valuable spermaceti oil inside their heads, which was used to make candles. Populations were undoubtedly depleted during this time, but currently this species appears to be fairly abundant in all oceans. Current threats include the accumulation of toxic pollutants such as organic pesticides in the whales’ tissue and organs, entanglement in fishing nets and marine litter, and noise disturbance, which interferes with their complex echolocation and use of sound. Sperm whales are protected under UK and EU law, principally under Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004 and by the 1992 EU Habitats and Species Directive.